Fair trade issues directly concern pearl and bead stringers fair more than any of us might have imagined.

Fair trade issues directly concern pearl and bead stringers fair more than any of us might have imagined.

For example, did you know that the strand of ruby beads you’ve just used in a necklace may have helped cause silicosis in a worker, a worker who may have been paid 11 cents for cutting and polishing that strand of beads and who may be still a child?

The colored stone industry, led by a few remarkable people, is beginning to tackle that question and others like it in a real and substantive way. And because as pearl and bead stringers we use colored stones in our jewelry, it’s an issue of importance to us and possibly to our clients.

The issues are at once simple and complex, global and local. Even identifying the “right” issues are the subject of heated debate within the industry. And, it’s important to note that whatever solutions can be arrived at in the end may be undercut by the secrecy that characterizes all niches in the trade.

First, let’s take a brief look at the colored stone industry. The dealers we see at shows are the tip of a very long spear. They may source colored stones directly from mines, may own mines, or they may be intermediaries who buy from exporters. Colored stones, including beads, are cut and polished by small shops all over the world and again, the dealer we see in his booth may operate his own factory or deal with multiple, also small, factories, factories which in turn source from multiple small and artisanal mines. (Artisanal mines are those where the workers aren’t officially employed by the mining company, but who work instead as independent contractors.)

This brief overview omits the finished goods manufacturer which adds another layer in the distribution chain and another potential layer of abuse. And it omits goods that are obtained, wittingly or unwittingly, from smugglers or from those who use colored stones to finance conflict or dictatorships.

Unlike the diamond trade where large companies dominate mining, although not necessarily polishing, the colored stone trade is fragmented at every step from mining to polishing to manufacturing to wholesale and retail distribution. And, at every step, there is potential for abuse. Here are some examples to illustrate the point.

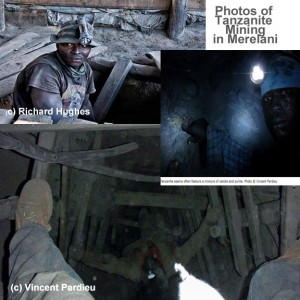

- Humangoods has done some excellent reporting on tanzanite mining conditions. Tanzanite, the lovely, rare blue-to-purplish stone that is sometimes compared with sapphire, is mined in a Tanzanian village called Merelani. Many of the 30,000 or so miners work in poorly constructed shafts for less than a dollar a day. In addition, various NGOs (Nongovernmental Organizations) report that at least 4,000 children work in those mines.

- The Institute for Global Labor and Human Rights reports that at least 2,000 men, women and children have died of silicosis in India polishing gemstones like rubies, sapphires, moonstones, agates, etc., for 17 to 33 cents per hour. These workers “dry” polish stones, that is, they don’t use water to grind which reduces the deadly dust. Why? They typically must pay the factory owner for water and electricity and it usually takes longer to produce a finished product with a wet grind.

- Environmental issues are a category of their own. The impact of mining is often misunderstood in third world countries where sustainable environmental practices are often ignored or misunderstood.

- Like diamonds, colored stones are often used to finance conflict. The most prominent example is the support of the military dictatorship in Myanmar, formerly known as Burma. The Taliban seized emerald mines in Pakistan’s Swat Valley to finance expanded operations.

The above is a very brief snapshot of some of the issues facing the colored stones industry. So, how does a fragmented industry, composed of mostly small companies and individuals, address these enormous issues?

There are a number of suggestions. Some want colored stones businesses to agree to Fair Trade protocols in which the business agrees to conduct itself in a socially and environmentally responsible way, including entering into producer price guarantees and investing in local social and environmental projects, among other requirements. The protocols also call for the company to submit itself to review by a number of entities including standard setting organizations, third party audit groups and finally certification-issuing groups.

While the above may sound reasonable, the protocols are unaffordable for small companies.

Others suggest transparency in the “chain of custody,” that is the documentation of responsible social and environmental practices at every step from the mine to the retailer. But how reasonable is it to suggest that a pearl and bead stringer, for example, commit the time and money to ensure best practices at this level? Should retailers, especially independents, be required to send people to far off countries to document mining conditions, and the operations of cutting, polishing and manufacturing companies. And, this assumes that the targets of these reviews would be cooperative which given the traditional secrecy of the trade at every level is problematic.

For a fragmented industry made up largely of small companies and individuals, there is no top down, one size fits all in determining an answer.

But there are points of light which suggest realistic solutions.

Columbia Gem House, under the leadership of Eric Braunwart, is demonstrating how a company can make a real and sustained commitment to responsible social and environmental practices without bankrupting itself.

If I understand the company’s policy correctly, it made a voluntary decision to incorporate Quality Assurance and Fair Trade Gems Protocols into its operations. Its webpage explains that “Fair Trade Gems are closely tracked from mine to market to ensure that every gem has been handled according to these strict protocols. The protocols include environmental protection, fair labor practices, health and safety standards, and a tight chain of custody that eliminates the possibility of treated gems or synthetics being introduced into the supply chain. The program also includes promotion of cultural diversity, public education and industry accountability.”

In a long discussion at the JCK Las Vegas show in June, Braunwart indicated that because the protocols are voluntary, the company has the freedom to make its own choices in supporting them. As an example, Braunwart discussed a village where the addition of one bull, that is a bull like a cow, made a huge difference to the living standards of that village. It’s unlikely that a top down protocol would mention a village’s need for an additional bull or a corporate obligation to supply it.

Braunwart and Mark Rapaport, founder of the influential Rapaport Diamond Report, and also a leader in raising industry awareness of the need for ethical industry-wide social and environmental practices, agree that real change will come when consumers demand it. They agree that it’s the responsibility of the industry to raise awareness of these issues and help create that demand.

Braunwart, Rapaport and others may not have all the answers yet. But they are working on developing them.

As pearl and bead stringers, our obligation is to monitor the Fair Trade colored stones issue and support the real efforts of these leaders to address them.