When we think of the Gilded Age, we think of the excesses of the wealthy a period from about 1870 to the turn of the century.

Great wealth accumulated as the Industrial Revolution catalyzed new industries, railroads, steel, mining, among others. Innovations abounded. Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone. Thomas Edison invented the phonograph and the light bulb. And, 1871 Mark Twain asked “What is the chief end of man? – to get rich. In what way? –dishonestly if we can; honestly in we must.”

Although Gilded Age excesses were seen all over the country, New York was the epicenter of what we think of as the period. And, although a 150 years later we may wince at its excesses, as jewelry designers we shouldn’t ignore the new styles produced in that period.

Some of the great designers of the period are names that are familiar to us. Louis Comfort Tiffany, Rene Lalique, Peter Carl Faberge are designers whose work we all have at least a passing acquaintance with.

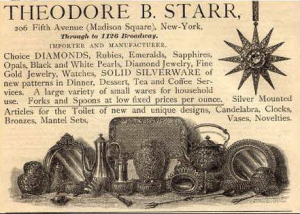

Other designers aren’t as well known. Theodore Burr Starr is one of those names. Starr was born on August 6, 1837 in New Rochelle, NY and was a partner from 1864 to 1877 with Herman Marcus in New York City, operating luxury retail outlet as Starr & Marcus. When Marcus left the firm to join Tiffany & Co., Starr worked from 1877 to 1900 as a jeweler and merchant in New York as Theodore B. Starr & Co. His son took over the business and in 1918 the company was bought by Reed and Barton, the silver firm. It closed its doors in 1923.

In 1882, the New York Times carried a piece entitled “Exhibition of Jewelry” describing Starr’s work. In it, the anonymous writer declaimed that art jewelry “Recognized as that art which must be in a certain measure indifferent to the costly materials which enter into its composition, it seeks to enhance the beauty of the gems and the gold by making them subservient to human skill. Barbaric and uneducated tendencies care for huge surfaces covered with stones, where crude masses of gold are displayed…”

The writer goes on to describe the exhibit as containing many “exquisite jewels. “riveres of diamonds,” a “bracelet of diamonds and emeralds and “pearls of various hues that the real magic of the jeweler’s art if brought most in prominence.”

There is more, of course. The writer concludes that “the exhibition of a great house which caters to those who are the most appreciative presents a class of artistic objects not second to those hung on the walls of a picture gallery.”

Unfortunately, I can find only a few examples of his jewelry whose provenance is clear. Far more images of Starr’s silver work are available. However those that I can find clearly illustrate the jewelry trends of the period, an interest in nature, colored stones and in the flowing lines we associated with Art Nouveau.

I should also add that for the most part, the little I’ve been able to uncover of his work suggests that at least in the jewelry area, his work is largely derivative, borrowing from the prominent themes and designs of the period. I could be absolutely wrong, here, though.

Despite that, the work is beautiful. Here are some images.