In an era where the cost of precious metals in a setting can often exceed the cost of the gemstone, it’s perhaps no surprise that manufacturers in the trade are moving to develop new and less expensive alloys for jewelry making.

One of these new alloys is “Platinaire,” developed by A.G. Weindling, a manufacturer. According to the company’s website, Platinaire is already sold in more than 3,000 stores nationwide. It is a patented alloy that combines sterling silver and platinum. The blend is 92.5% silver and 5% platinum and 2.5% the undisclosed elements that make up the patent. The metal is being promoted as a cost efficient alternative to gold for engagement rings although the company promises to introduce a full line of jewelry in the future.

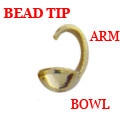

However well Platinaire does in the marketplace it’s important to have an understanding of the properties of its two precious metals. Pearl and bead stringers almost certainly use sterling silver in making jewelry and although we don’t use platinum as much, we do incorporate it into designs with higher end gemstones such as South Seas Pearls. Here is a brief review of the basic properties of these two precious metals.

Sterling Silver: A Complicated Relationship for Jewelry Makers

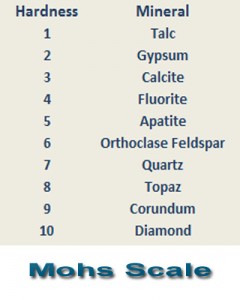

Sterling Silver is composed of 92.5 percent fine silver or pure silver and 7.5 percent copper (usually). The copper is added to the fine silver to harden it, to give it strength and durability.

Sterling Silver is composed of 92.5 percent fine silver or pure silver and 7.5 percent copper (usually). The copper is added to the fine silver to harden it, to give it strength and durability.

Fine silver is somewhat reactive, Although it doesn’t tarnish easily, it does react with sulfur compounds in the air and our sweat to form black silver sulfide. But the tarnishing we are all familiar with is a result of the copper alloy. Copper is highly reactive–it tarnishes and forms copper oxides very easily.

The copper in the silver is what makes silver’s relationship with jewelry makers complicated. Sterling silver is easy to work with. It’s extremely malleable and ductile and it’s also the least expensive of the precious metals. But it tarnishes.

Related to this is the issue of firescale or firestain, a reddish purple bloom or stain that can occur on sterling silver when it’s heated in the presence of oxygen. Although silversmiths use a variety of methods to avoid firescale, it does occur when the silver is heated and can destroy or at the least change the appearance of a piece.

By the way, the 92.5 percent standard was set in England around 1300 and silver’s association with the British pound sterling lead to its name “Sterling Silver.”

Interestingly, silver has a special place in the history of the elements because it is one of the first five metals discovered and used by humans. The others are gold, copper, lead and iron. The oldest silver objects have been found in Greece and date back to 4000 bc.

The necklace pictured above is of the Cullinan Diamond necklace, a necklace made from pieces of the monster diamond — total pre-cut weight of 3,106.75 carats — discovered in 1905 by Thomas Cullinan. This necklace was a gift to his wife. Please notice the silver settings.

Platinum: First Among Equals…by a Wide Margin

Platinum was first discovered in South American in the sixteenth century by Spanish conquistadors who regarded the metal with some contempt, naming it “platina” meaning little silver. In fact, when the Spanish encountered the metal while panning for gold, they threw it back to allow it to “ripen” into silver.

It wasn’t until the middle of the eighteenth century when the metal reached Europe that platinum began to receive the attention it deserved. In 1751, Swedish scientist Theophil Scheffer categorized platinum as a precious metal and by the 1780s Louis XVI declared it was the only metal fit for kings

What made platinum so attractive to European royalty are the same properties that makes platinum attractive today. It is beautiful to look at, a silver-grey shiny metal, but it is relatively non-reactive, meaning it doesn’t combine with or interactive with other chemicals or compounds. This means it’s highly resistant to tarnish and corrosion.

Platinum is also ductile and malleable. This is important. A ductile metal can be drawn into thin wires while a malleable metal can be hammered into thin sheets. The trouble for early users of platinum, though, was that platinum’s high melting temperature meant that it couldn’t be rendered malleable for jewelry. (Ordinary furnaces of the time didn’t get hot enough.) As a result, it’s use was limited to decorative items.

In 1856, the high temperature jeweler’s torch was invented. The oxyhydrogen torch made possible the high temperatures needed to solder, melt and cast platinum. When diamonds were discovered in Kimberly, South Africa in 1866, it quickly became apparent that platinum complemented diamonds in a way that gold and silver could not. Despite this, the availability of platinum was extremely limited. Columbia had stopped exporting it in 1822 and the only source of platinum in the 19th century was its discovery in the alluvial gold mines in the Ural Mountains.

Platinum jewelry was popularized in the early twentieth century by the French firm Cartier. Louis Cartier used platinum in his “Garland” style pieces and to enhance the brilliance of diamonds. His work is so successful that it became synonymous with the Edwardian jewelry which was characterized by pearls, diamonds and platinum. In fact, Edward VII said of Cartier that he was “the jeweler of kings and the king of jewelers.”

Cartier himself described platinum jewelry as “embroidery,” a term which he felt conveyed the airy delicacy which could be achieved by the metal. Platinum made it possible for the jeweler to create mounts and settings as light as they were strong. In fact, some of the settings created by Cartier are so fine as to be almost invisible. In evaluating this achievement, remember that diamonds had been set in sterling silver. Because sterling silver is soft, jewelers typically used somewhat clunky, unattractive mounts to protect the gemstone.

Cartier himself described platinum jewelry as “embroidery,” a term which he felt conveyed the airy delicacy which could be achieved by the metal. Platinum made it possible for the jeweler to create mounts and settings as light as they were strong. In fact, some of the settings created by Cartier are so fine as to be almost invisible. In evaluating this achievement, remember that diamonds had been set in sterling silver. Because sterling silver is soft, jewelers typically used somewhat clunky, unattractive mounts to protect the gemstone.

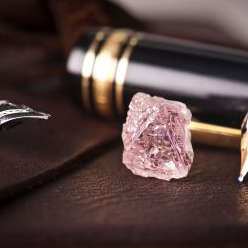

Platinum’s strength is illustrated by the fact the some of the most important diamonds in the world are set in platinum. The Hope, Jonker Diamond Number One, and the Koh-i-Noor, are all secured by platinum settings.

Today, three quarters of the world’s platinum output is sources in South Africa from the Bushveld Igneous Complex. Platinum is also sourced, to a lesser extent, from Canada.

It is one of the rarest materials on earth.To produce a single ounce of platinum, a total of 10 tons of ore must be mined. In comparison, only three tons of ore are required to produce one ounce of gold.

Most of all, it’s beautiful. It’s rich luster and neutral color complements and enhances gemstones, especially diamonds.

Conclusion

We’ll see how “Platinaire” does in the marketplace. A number of new sterling silver alloys have been created in recent years with varying degrees of success. However, it’s important for jewelry makers, including pearl and bead stringers, to know the properties of precious metals and be able to discuss them with clients.