As pearl and bead stringers, we may use diamond beads in our jewelry. However, apart from whether we use them ourselves, diamonds are a key part of the jewelry trade, familiar to everyone, and desired by most.

As pearl and bead stringers, we may use diamond beads in our jewelry. However, apart from whether we use them ourselves, diamonds are a key part of the jewelry trade, familiar to everyone, and desired by most.

This means that we must familiarize ourselves, at least broadly, with major issues affecting diamonds so that we are prepared to discuss them with clients.

“Blood diamonds” is one of those issues where it’s vital you have an informed response to a client query.

The following is offered as a broad backgrounder to the issue of blood diamonds and the extremely fragile status of the Kimberley Process, the solution to blood diamonds developed by governments, the industry and various NGOs (non-governmental organizations).

The “Blood Diamond” Background

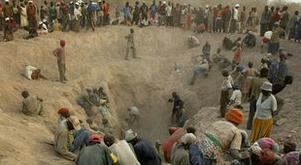

The Kimberley Process developed in response to wide-spread repugnance at brutal practices associated with “blood diamonds” – diamonds that fueled conflict in Africa, especially Sierra Leone, in the decade of the 1990s.

In the West, mainstream journalists became interested in the conflict in Sierra Leone and also in Angola and began reporting on it. Various human rights organizations, including Global Witness, Amnesty International and Partnership Africa Canada, publicized the brutality. A prominent Congressman (Tony Hall D-Ohio) helped draw attention to the issue. And, nearly a decade after the outbreak of conflict in Sierra Leone, the United Nations passed a resolution supposedly “breaking the link” between illegal diamond trade and armed conflict.

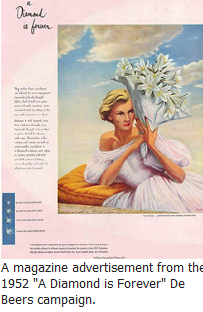

Consumers, now educated on the subject, began to demand something be done. In this country, diamonds are permanently associated with engagement rings and for obvious reasons people did not want a tainted gemstone. (Conflict diamonds later became a suspected source of funding for al Qaeda, however, that did not become a concern until after the Kimberley Process was established.)

The Kimberley Process

In May, 2000, governments, NGO (non-governmental organizations) and the diamond industry came together in Kimberley, South Africa (where large scale diamond mining began about 150 years ago) to endorse the Kimberley Process. The aim of the process was to halt or at least effectively combat trade in conflict diamonds. To accomplish this, the process calls for:

- Shipments of diamonds in tamper proof containers accompanied by a government approved Kimberley Process certificates.

- Tamper proof certificates that cannot be forged;

- Exports (shipments) only to countries participating in the Kimberley process.

In all, 52 governments signed off on the Kimberley Process. The Kimberley Process can also call for restrictions on nations in which human rights violations occur.

Current Blood Diamond Issues

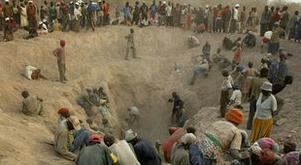

In 2011, the focus of the Kimberley Process has shifted from Sierra Leone to Zimbabwe’s Marange Valley, home to vast alluvial diamond fields worth up to $800 billion, according to some estimates.

In 2011, the focus of the Kimberley Process has shifted from Sierra Leone to Zimbabwe’s Marange Valley, home to vast alluvial diamond fields worth up to $800 billion, according to some estimates.

And, the Kimberley process, once hailed as an example of cooperation between governments, NGOs and the industry is, according to one trade publication, “disintegrating before our very eyes.”

The Marange Valley deposits were discovered in 2006. Ironically, DeBeers once owned the mining rights to the 46 square mile area, but let them lapse over concerns about Zimbabwe’s political and economic crises and because it believed there were no significant deposits in the area.

In 2008 the Mugabe government seized the fields, killing 200 people in the process. And, immediately reports began to surface of human rights abuses, including rape, child labor and mass killings as the government forced locals to work in conditions approaching slave labor.

In 2010, over the objections of the United States and the World Diamond Council, two Kimberley Process sanctioned diamond auctions were held. Currently, the Process is at an impasse and some press reports indicate that Zimbabwe, which regards the KP as “nonsense”, and its potential diamond buyers are simply waiting for the KP to crumble.

Marange Valley diamonds are making their way to cutting centers around the world in a couple of ways.

- The Zim government recently made a deal with China, signed in March, giving away rights to diamonds worth $98 million in exchange for the construction of a defense college for the military.

- Millions of dollars in smuggled diamonds are making their way to Surat, India which is rapidly becoming one of the world’s largest cutting centers. Press reports indicate that Marange Valley diamonds are also turning up in Antwerp.

Source of the Problems

Despite the best efforts of Kimberley Process participants, the Marange Valley issue has exposed a number of perhaps fatal flaws.

Despite the best efforts of Kimberley Process participants, the Marange Valley issue has exposed a number of perhaps fatal flaws.

- The government of Zimbabwe considers the Kimberley Process an intrusion into its internal affairs and several of its officials in fact have called the process “a human rights violation.” Zim is not alone in wanting the Kimberley Process to “just go away.”

- The effectiveness of the process depends upon voluntary governmental participation. Where there is no government participation, remedies are ineffectual. China, for example, is not a participant in the Kimberley Process.

- Internal strife has also weakened the Process. The current president, Matthieu Yamba of the Democratic Republic of Congo, has supported unsupervised diamond sales from the Marange Valley, prompting NGOs and others to walk out of key meetings designed to resolve the issue. The rift has grown so bitter, according to trade reports, that it may be impossible for NGOs to work with the Process.

- Key industry groups are disengaging. The World Diamond Council, a key industry player, is reportedly preparing a statement criticizing the KP and its leadership, something it has never done before.

Meanwhile, violence has broken out in Central African Republic Diamond fields, violence that has industry observers worried that about full scale civil war.

What to Tell Clients

The Kimberley Process has been criticized as a public relations stunt by the diamond industry. That’s not true. Up and down the chain of custody, the trade is committed to supporting ethical mining practices. The Rapaport Group, for example, has said it will expel members of its global Rapnet diamond trading network if they sold Marange Valley diamonds. Moreover, most retailers here and in Europe attempt to sell only certified diamonds.

The key pressure point, therefore, is not the trade, nor is it the participants in the Kimberley Process. It is the corrupt and renegade governments that torture their citizens for power and private gain.

Nevertheless, consumers can help keep the blood diamond issue alive. Advise your clients to ask retailers if the diamonds they are selling are certified.

Keeping up the pressure is the best way to ensure a continued commitment to keeping diamonds conflict free.